Artist Rowena Federico Finn Comes Out of Her Shell

Rowena Federico Finn teaching a Color Mixing Workshop (Photo by Charles H. Taylor, Visual Arts Center)

This journey has been long in the making. Early in her career, Rowena painted realistic botanical watercolors, but she eventually realized she wanted to create art that connected more closely to her Filipino heritage. The daughter of Rodolfo and Erlinda Federico, Rowena grew up with her older sister, Rachel in Hampton Roads, Virginia Beach, home to a large Filipino American community. Her parents helped establish the Philippine Cultural Center of Virginia and several Filipino American organizations, and Rowena recalls “vivid memories of rolling lumpia” for countless community parties.

Despite being immersed in Filipino culture and appreciating her parents’ contributions, Rowena often felt she didn’t belong. She describes herself as “introverted and shy,” preferring to make art rather than participate in the performing arts. Decades later, she finally found a community where she felt wholly herself through the Norfolk Drawing Group at Norfolk State University. She also joined the Hampton Roads chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), drawn to its mission of preserving history with honesty and care.

Rowena’s family (Photo Courtesy of Rowena Federico Finn)

A Fine Arts graduate of James Madison University, Rowena has always been drawn to creating with her hands. As a child she built with Legos, sculpted with polymer clay, and constructed forts from sticks. A book about Leonardo da Vinci became one of her earliest influences, she remembers thinking, “I would love to be as good as he is, to be able to draw and paint that well.” Her path to a Fine Arts degree was not straightforward. She began as an Anthropology/Archaeology major to satisfy her parents’ wish for practicality. She later convinced them that Graphic Design was employable, and from there she gradually shifted to Fine Arts, where she earned her degree.

After a 2023 trip to the Philippines, Rowena decided to experiment with materials tied to Filipino culture. One of the materials available online was capiz, the shell of the windowpane oyster. She developed a portfolio of mixed-media art grouped into four categories: Capiz Quilts, Balut, Capiz Waves, and Alchemy. She wanted to elevate capiz, which she associated with seaside souvenirs, into fine art. She likens the shells to people: “sturdy” yet “delicate,” revealing their true nature only when examined closely. After sourcing workable shells from Etsy (Amazon’s were too thick), she began cutting them into squares reminiscent of quilts. These quilts, drawing from the warmth and communal spirit of American folk traditions, invite viewers to take a closer look.

Rowena’s own family (L-R) husband Mike, Melanie, Rowena, Molly and Jasmine (Photo Courtesy of Rowena Federico Finn)

Rowena describes her work as “Filipina Futurism,” “creating a new visual and cultural language—one that speaks to the experiences of being neither fully from one land nor the other and forges a path that bridges histories and redefines tradition.” This sentiment shows in her work which is deeply personal but also emblematic of generations of Filipino Americans who grew up in the United States. Her capiz quilts juxtapose her own stories with shared Filipino and immigrant narratives. A recent American University Museum exhibit underscores a similar sensibility, featuring Filipino American multimedia artists like Mic Diño Boekelmann, known for her use of Manila envelopes, and Jeanne F. Jalandoni, who incorporates fabric into her paintings.

While Rowena feels grounded in her American identity, she recognizes how little she knows about her Filipino roots. Today, young Filipinos in Hampton Roads have access to cultural programs at the Philippine Cultural Center of Virginia, and educators can download Filipino American and Philippine history materials from FAHNS–Hampton Roads, a resource Rowena never had as a child.

Close-ups

The Stories We Tell Ourselves (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

Many of Rowena’s Capiz Quilts nod to her childhood love of fairy tales through Fritz Keidel’s illustrations that are framed in each capiz shell; fittingly, Keidel himself was an immigrant. In The Stories We Tell Ourselves, Rowena’s jewelry-making background (she is an Accredited Jewelry Professional through the Gemology Institute of America) emerges in the gold chains and meticulously placed beads framing each illustrated shell. She deliberately uses Western fairy tales, explaining that she grew up knowing none of their Filipino counterparts. Though she states this matter-of-factly, there is an undertone of regret, “Why was this part of her heritage not shared with her?”

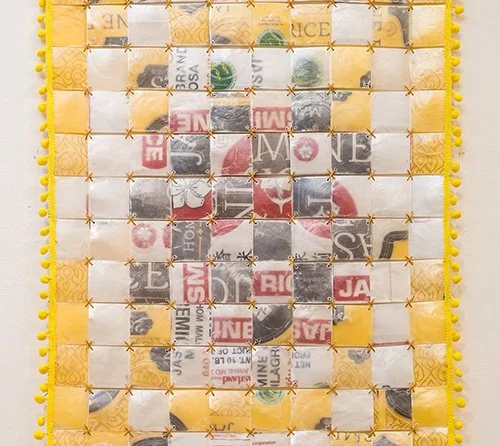

Sugar and Spice and Everything Rice (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

Rose Colored Glasses (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

Her playful side shines in Sugar and Spice and Everything Rice (That’s What Filipinas Are Made Of), a bright, cheerful work using rice bags and piña. It marks her first successful attempt to make capiz appear more quilt-like; her earlier efforts involved soldering the shells together. The piece also serves as a tongue-in-cheek response to stereotypes of Filipinas as subservient or delicate. Rowena, who is equally skilled with power tools and needle and thread, admits she asks “too many questions,” even as an introvert. In Rose Colored Glasses, she fashions a pair of spectacles adorned with tiny roses and Swarovski crystals, another meditation on identity and the ways perception can be obscured, seen, perhaps, through “rose-colored glasses.”

Life Interrupted (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

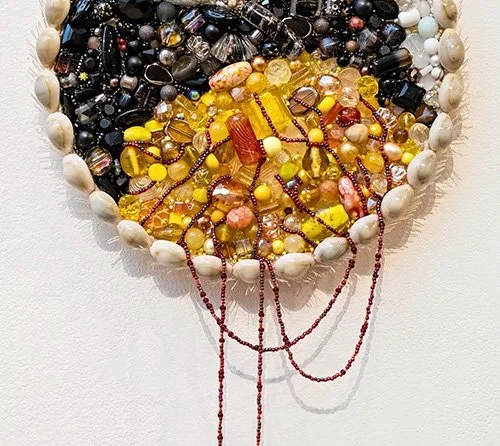

In her Balut series, Rowena confronts eating balut, the fertilized duck embryo, a traditional Filipino snack that is popular, but also invites controversy. She playfully recreates the balut using yellow, white, and black beads, making it palatable for the uninitiated. Her titles–Transfer of Power, The Beginning and the End All in One Bite, Life Interrupted, and This Isn’t How I Thought It Would Be –address the unsettling act of eating a whole duck embryo.

Turbulence (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

Her Capiz Wave series experiments with the shells to create rippling forms resembling waves and surprisingly, soft fluffy feathers. In Turbulence, Rowena visualizes opposing forces: two cultures tugging at each other, or the tension between family expectations and personal truth. She thinks of the ocean as a single body whose waves push and pull unpredictably, much like life, where things do not always fit neatly together.

‘My Dinner with Carlos’

My Dinner with Carlos (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

My Dinner with Carlos pays homage to Filipino American artist and educator Carlos Villa (1936–2013). The feathers reference is a nod to Villa’s use of feathers in his own work. Villa rebuilt what he was once told did not exist: a Filipino American art history. His contribution to the Asian American artistic landscape is recognized in the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects. (The only other Filipino American visual artist in the book is Stephanie Syjuco.)

Growing up, Rowena never encountered Filipino artists, and Villa’s work struck a deep chord.(Pacita Abad is another source of inspiration) She felt a kinship with Villa, who like her was born to Filipino parents in the United States, and was also trying to define an identity straggling two cultures. Like Villa, she is also an educator. She teaches visual arts at the prestigious Governor’s School for the Arts in Norfolk and is a Teaching Artist for the Virginia Commission for the Arts, an experience she believes makes her a better artist as she teaches students the basics of drawing and mixed media. Her presence provides representation for aspiring Asian American students. She fondly recounts a former student who told her he was “floored” to see her reviewing his portfolio, the first time he had ever seen an adult Filipino American professional artist.

The ‘Anitos Quilt’

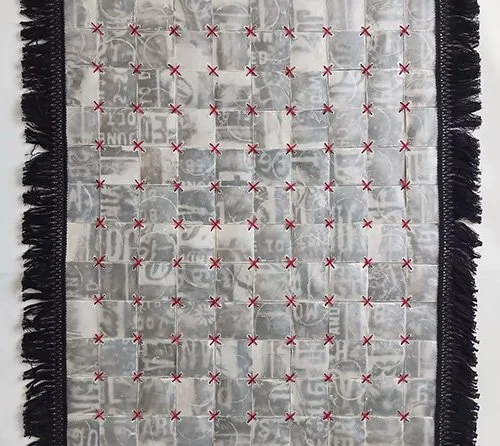

Anitos Quilt (Photo by Rowena Federico Finn)

The most personal of Rowena’s works is the Anitos Quilt, a love letter to her children Melanie, Molly, and Jasmine. Measuring 22 by 29 inches, it is formed from curved capiz shells stitched front and back into a puffy quilt, with piña cloth inside for support. Embedded within are grave rubbings she made of her grandparents’ headstones when she visited the Philippines in 2023, arranged in multiple directions to keep the inscriptions intimate and somewhat unreadable. The quilt serves as a symbolic security blanket for her children, representing the protection from the spirit of ancestors long gone.

Rowena once believed she would never part with the piece. But when Chelsea Pierce, McKinnon Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Chrysler Museum of Art, reached out as part of the museum’s initiative to better reflect its community, she asked if Rowena had a work she might want included in the collection. Rowena had long noticed the absence of Filipino artists in the museum. (They later discovered a work by Filipino American artist Paolo Arao, Electric Oasis, currently on display.) Having the Anitos Quilt acquired by the Chrysler meant the piece would be preserved and shared with the community she grew up in, giving Filipino viewers the chance to see themselves reflected in its halls, something she never experienced as a child.

She describes herself as “introverted and shy,” preferring to make art rather than participate in the performing arts.

Though Anitos Quilt is not currently on display, it was featured in a special exhibition together with British Artist Zoe Buckman and American Impressionist Mary Cassatt - Forging Paths: Grounded by Memory,” curated by the museum’s summer interns last August.

In Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects, Theodore Gonzalves quotes Carlos Villa: “The artist—the artist/cultural worker—can serve as a conduit to their communities, as opposed to being merely documentarians or specialists.”

Rowena Federico Finn, who once felt she didn’t belong in the Filipino American community of her childhood, has now become not only a member of that community but one of its most dedicated advocates.

To learn more about Rowena Federico Finn, visit her website here or follow her on IG here.

Find her work at the Where We Meet exhibit at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art until January 11.

Titchie Carandang is a freelance writer. Her articles have been published in the White House Quarterly, Northern Virginia Magazine, Metro Style, Connection Newspapers and other publications. She is the co-founder and was co-director of the Philippines on the Potomac Project (POPDC), where she researched Philippine American history in Washington, D.C. She has received awards from the Philippine American Press Club, the Mama Sita Foundation, and the Doreen Gamboa Fernandez Food Writing Award for her writing.

More articles from Titchie Carandang

No comments: