A Book on the First Filipino Olympians–Or Is It?

While we won’t be seeing the Men’s Curling team nor what would have been the first Filipino Pairs Figure Skating team (of Isabella Gamez and Alexander Korovin) compete, the country will still be represented by newer and younger blood on the slopes.

Tallulah Proulx, a Fil-Am, grew up in Park City, Utah—so she was born to ski, and at 17, will be the youngest, will be the youngest Filipino Olympian, winter or summer. Accompanying her on the slalom and giant slalom courses will be Francis Ceccarelli, who will be schussing the slopes of his second home, Italy. Ceccarelli, now 22, was adopted from Quezon City when he was eight by Italian parents and moved there. His adoptive mother was a former professional skier, Lisa Seghi.

So, Proulx and Ceccarelli will probably be marching in the Cortina Opening Ceremony since they are splitting the athletes in both Milano and Cortina.

‘Filipino Olympians’ Book, a Missed Opportunity

A few months ago, a curious “Olympic” publication appeared in Manila. I had been waiting for a book like this for the last year—nay, the last two years. Where has it been all this time?

Published by Archivo Press, 2025

As a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH), I was tasked in 2023 to write about the centennial participation of the Philippines at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games. It would’ve been a special anniversary and that article would have been for the Paris 2024 issue of the ISOH Journal.

The 1924 Paris Games are among the most celebrated Olympic Games editions of the Modern Era for they were immortalized in the highly successful, Oscar-winning film of 1981, Chariots of Fire, whose depiction of the Abrahams-Eric Lidell-conflict (that running on the Sabbath was a problem for Lidell), was greatly tweaked for dramatic purposes. Obscured too, is the fact that the film was co-produced by the late Princess Diana’s last lover, Dodi Fayed, who perished with her in the Paris tunnel (fatefully ironic, wasn’t it?) in 1997. But that’s a story for another day.

For those who look at international events like these from a purely “statistical” point of view, the Philippines was one of nine new lands or territories which made their Olympic debut at Paris 1924. The other new “Olympic virgins” that year were Bulgaria, Ecuador, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Uruguay.

But like many international events wanting to be taken seriously—including beauty pageants which Filipinos love so much—early organizers take all and every newcomer (regardless of actual international standing) just to have good numbers to start out with and then refine the membership requirements as you go along.

I was excited about writing the centennial-marking project and gave myself more than a year to prepare for it; but I also, of course, sought more than anything else, some input from the Philippine Olympic Committee (POC) who would benefit most from the exposure. I figured the POC would be the natural source of appropriate material.

Months passed and as 2024 neared, I got nothing—no feedback, no replies from the POC whatsoever. Did I overestimate the worth of the POC as the most natural and reliable font on its own history? I must have. Long and short of it, 2024 came and went and there was no appropriate anniversary article about the Philippine centennial participation in the Olympics in the ISOH’s Journal last year.

But now, all of a sudden, since September 2025, Archivo Press, a small, independent publisher back in Manila, published The First Filipino Olympians (The Untold Story of Dr. Regino Ylanan and David Nepomuceno)—part of what I was definitely looking for, for the failed centennial article.

I was lucky enough to have been gifted an advance copy of the book, but it was a very challenging, frustrating, and ultimately confounding work.

The USA’s Stars & Stripes over the Philippine tricolor—probably the first and only time in Olympic history, this was allowed. (This photo is in the public domain.)

At first glance, and after first perusal, the “book” strikes me more as a monograph than your traditional “book.” Without getting petty about it, but to be precise—as I would want this publication to succeed and be taken seriously in the sports-chronicling world, here are what struck me first:

(i) what a strange size Archivo Press gave it—even though no expense was spared in the quality of the paper for its 210 pages, used.

(ii) no authors or editors are listed on the cover. Why?

(iii) the book carries an ISBN number but no price (which must be the current practice now, to account for price changes).

To be fair, the book is chock-a-block with information about Dr. Regino Ylanan—probably the first full-time compleat Filipino sports administrative professional who as a young athlete-medical doctor-sports administrator, ran the full gamut of all the stages required in bringing a fledgling Third World republic up-to-code and aligned with international sports standards.

The Ylanan family made available the very comprehensive background material of their patriarch for the book. Dr. Regino Ylanan indeed had an exemplary and illustrious career, among other things, as a medaled track-and-field athlete in the early Far Eastern Olympic or Championship Games (precursor to the post-WWII Asian Games); as a coach. He also earned his MD at the University of Philippines in 1918 and a Bachelor of Physical Education from Springfield College, Massachusetts (where modern-day basketball and indoor volleyball had its origins) in 1920, and accompanied the nascent Philippine Olympic team in at least three Summer Olympics (Paris 1924, Berlin 1936, and Helsinki 1952). He became the first Director of Physical Education back at U.P., before “sports administration” became fashionable or even an accepted professional discipline.

Thus, a more accurate and fitting title for this time would’ve been The Complete Memoirs of Dr. Regino Ylanan, Filipino Sports Administrator Extraordinaire. But once the reader gets past the whole Ylanan saga, it makes one wonder why they threw everything against the wall and hoped most of it would stick?

With Ylanan’s bio, First Filipino Olympians really only tells half the story. The actual and only athlete, David Nepomuceno, who did the grunt work of running in the actual Paris 1924 Olympic track, is only afforded a few pages.

Not much is known or survives about Nepomuceno since he passed away at 40, some 16 years after competing in Paris. There is a yawning gap between the very full, documented career of Dr. Ylanan and the paltry information on the true first Filipino Olympic athlete who sadly finished dead last in both his heats (for the 100-meter and 200-meter sprints) on the 1924 track. So, the title The First Filipino Olympians feels slightly disingenuous. A more accurate and fitting title would’ve been The Complete Memoirs of Dr. Regino Ylanan, Filipino Sports Administrator Extraordinaire.

The final quarter of the book is devoted to the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex which, indeed, holds a hallowed place in Philippine sports history; but sneaking it in as part of the main narrative, is a rather clumsy and obvious afterthought move.

(A small bit of credited forgetfulness here: the second edition of Holiday on Ice appearance in Manila at Rizal Memorial in 1955, page 190, was supplied by this author and acknowledged by co-author Lico, yet is not noted anywhere in the book. Symptom of the slap-dash editing of this tome.)

Most confounding of all is the sheer “lost” look of the “book” with many major faux pas:

• No authors (or editors) are listed on the cover. One has to dig inside to find who the accredited authors/editors are: Isidra Reyes, Gerard Lico, and Lorenzo Manguiat. I don’t know how that would sit with catalogues in the publishing industry or Books in Print, the bible of the book industry. Did Archivo Press not think of that?

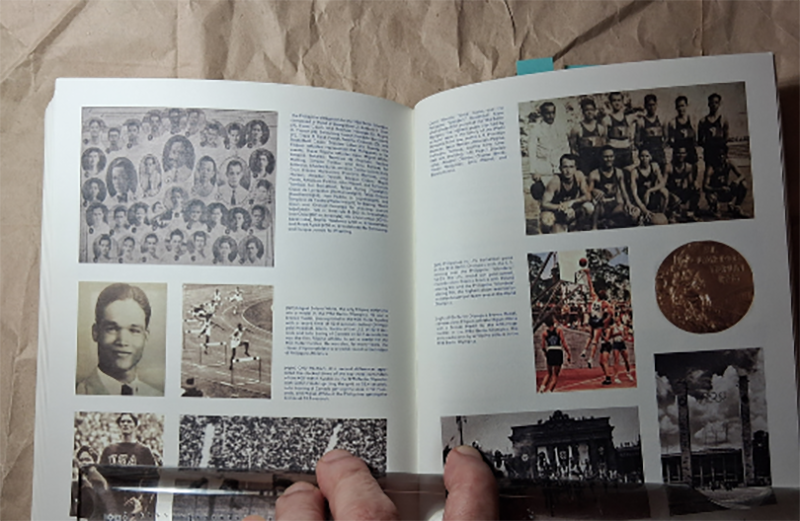

• As mentioned earlier, the Ylanan family gave unfettered access to Dr. Regino’s admirably detailed memoirs and files that there is a plethora of images and graphic documentation. For the first ¾ of the book, many of the photos and images are properly captioned although in 2-pt-size typeface font, so that a magnifying glass is required lest the reader go cross-eyed. Yet, in the final quarter dealing with the Rizal Memorial Complex, nearly all of the photos have no captions whatsoever and one is left to hunt for clues in the body text for the images to make any matching sense. Why put the reader through that? Did the editor quit halfway through and put in no replacement?

Photos in the earlier Ylanan part of the book are marvelously and greatly captioned but in tiny 2-pt font type-face.

Then, inexplicably, in the 2nd half dealing with the history of the Rizal Memorial Sports Complex, the photo captions have vanished and the reader is left with the task of linking said photos with the narrative in the body text. Huh??

Just before writing this review, I attended the monthly meeting of my local writers group featuring a New York-based published author and reader for the U.S. publishing industry as speaker for the month. Her topic was “Finding the Right Agent,” and in it she stressed that the U.S. publishing industry (the dominant market in the world) is very traditional in its practices and norms in order to turn a profit.

It is supremely ironic that a book celebrating the career of a guiding force behind a young country or territory’s growing pains—its attempt to adapt and find a place within a global sports order controlled, codified, and dominated by Europeans and North Americans—should itself violate nearly every established standard, norm, and practice of the international publishing world. Those very standards might have made it an accessible, credible, and formidable resource. One is left to wonder whether an unconventional presentation is meant to mask the thinness of the content or its occasional failure to hit the mark.

I had been waiting for a book like this for the last year—nay, the last two years. Where has it been all this time?

For readers seeking to understand the origins of Philippine sports in their modern form, and how these developments fit within the broader, hierarchical global Olympic structure, this is the book to consult. That said, I would caution the eager reader: acquiring the book—and, once obtained, reading it in a conventional way—will be a considerable challenge.

The publication defies virtually all reasonable and traditional formatting standards of the book industry and would have benefited greatly from judicious editing. Despite these shortcomings, I nevertheless wish the book well.

The First Filipino Olympians is available from the Archivo Press website: Archivo 1984

SOURCES:

Alpine skiing and the Filipinos competing in it at this year's Winter Olympics | Philstar.com

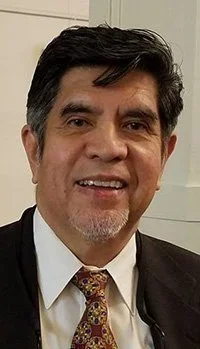

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. He has written three books:

· Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2021);

· Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes (© 2016); and

· Of Adobo, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles (© 2018)—all available in paperback from amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, UK and Europe).

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians, contributing to the ISOH Journal, and pursuing dramatic writing lately. For any enquiries: razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia

No comments: