‘Oakland Ilokana’: Recovering a Life Story

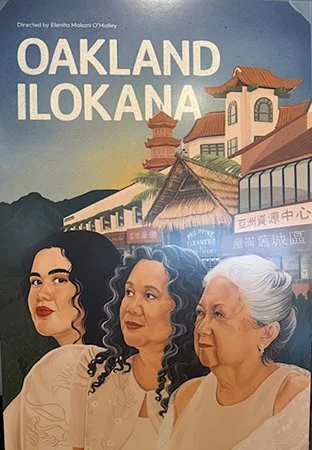

Oakland Ilokana Poster (Photo By Lisa Suguitan Melnick)

Marie Veronica Mendoza Rivera Yip, aka Lola Marie, was one of the first Filipino children to grow up in Oakland’s Chinatown. The film’s premiere at the beautiful Oakland Asian Cultural Center on October 4, set a meaningful tone of true community connection.

Elenita Makani O’Malley and Marie Veronica Mendoza Rivera Yip aka Lola Marie (Photo by Alyssa Cortez)

Born in Oakland’s Chinatown in 1934—the same year the Philippine Independence Act was signed—Lola Marie didn’t set foot in the Philippines until she was in her 50s. The Act, while paving the way for the Philippines’ eventual independence, also restricted the movement of Filipinos living in the United States. Those who left could not return unless they intended to stay in the Philippines permanently. Faced with that choice, Marie’s parents chose to remain in America.

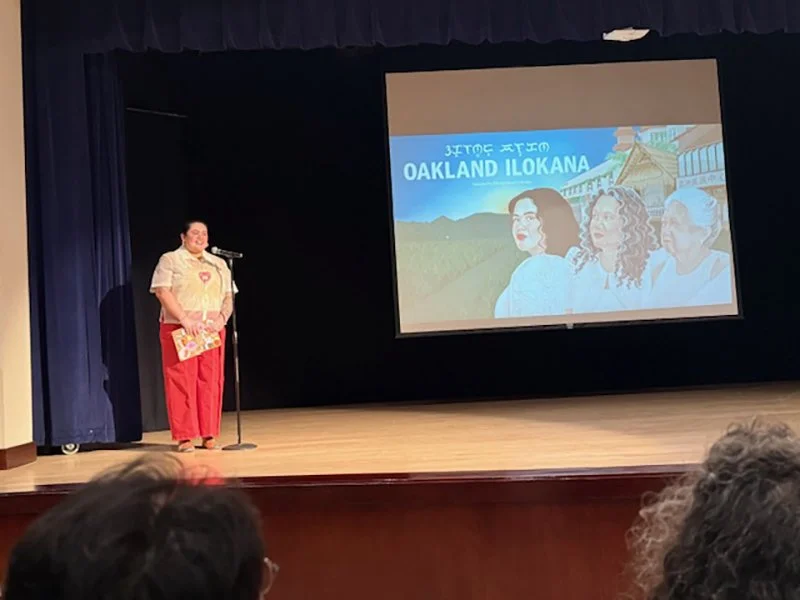

The filmmaker demonstrates an attuned sensitivity in portraying her lola’s resilience and complexity—holding the tension between hardship and fulfillment that defines her life’s narrative. O’Malley describes the film as “a legacy artifact,” created to ensure that future generations can hear her grandmother’s stories firsthand rather than through distant retellings. She also reveals that her lola is facing health challenges, adding a sense of urgency to the project and underscoring the care and responsibility O’Malley brings to preserving her family’s history. Beyond Oakland Ilokana itself, the filmmaker hopes the documentary encourages viewers to reflect on how they might connect with and listen to the elders in their own families and communities.

“I came to it as humbly and as earnestly and as gratefully as I could. And that I think can be challenging in family discussions, to really ask a question and be open to the answer and not decide what you think they’re going to say or decide how you think they did something in the past. Really give people the space to be full people, O’Malley explains.”

O’Malley never could have imagined how this project would unfold; once she immersed herself in it, it consumed her—body, mind, and spirit. She found herself constantly hearing her lola’s voice, especially during the long hours of editing. “I began to hear things within lola’s voice—the way she intones,” she says. She could catch her little jokes, her warmth, her rhythm. That voice now stays with her wherever she goes. When O’Malley faces life’s challenges, she can still hear what her lola would say.

O’Malley’s mother, Christine Nicholas, appears at several points in the film but remains outside the main focus. Behind the scenes, however, O’Malley shares that she and her mother have been uncovering family histories together—alongside a deeper understanding of broader Filipino historical narratives. As it turns out, most relatives hadn’t inherited the stories O’Malley longed to hear when she was younger, a result of what she describes as a “legacy of silence,” shaped by complex life circumstances.

O’Malley, her mother Christine Nicolas and Lola Marie (Photo by Alyssa Cortez)

Lola Marie grew up feeling unwelcome in America, surrounded by only a small community. She lost her mother at 12, which further severed her family connections and left her without the stories that anchor a lineage. As a result, she was unable to pass down much family history to her daughter, Christine. Christine’s father, originally from Manila, was the son of a Visayan woman and an African American soldier, and he lived in the Philippines until his twenties. When he immigrated to the United States under the War Brides Act of 1945, he chose not to speak about his life in the Philippines, having endured deep traumas in the aftermath of World War II. Consequently, O’Malley’s mother, Christine, inherited little in the way of cultural grounding from him.

“Before this film, Lola had never even pointed out a photo of her own parents, and now I know what her parents looked like. The film is a gift that will keep giving for years to come. My family will truly be able to get her stories from her own voice. That is something I’m truly grateful for.”

Although O’Malley’s mother, Christine, serves as the chronological bridge between her and Lola Marie, it is O’Malley’s “mission to break through and reach for the stories we still have access to” that ultimately makes her the true conduit between generations.

When O”Malley first set out to create Oakland Ilokana, she was searching for a sense of belonging—a rootedness in her identity that had long eluded her. She found herself questioning why family stories had never been fully accessible. Had she not listened closely enough? Were the stories deliberately withheld? Had her relatives simply chosen not to pass them down? Seeking answers, she turned to Lola Marie, whose unwavering sense of self and quiet strength drew her in. In the process, O’Malley discovered unexpected reflections of herself in her grandmother’s life—one of them being their shared connection to Oakland’s Chinatown.

O’Malley discovered unexpected reflections of herself in her grandmother’s life—one of them being their shared connection to Oakland’s Chinatown.

For instance, Lola Marie’s mother owned one of the first Filipino businesses in Oakland’s Chinatown. As a child, O’Malley would often buy egg tarts from the shop that now occupies that very same building—unaware that her great-grandmother once lived in the small room behind it. Lola Marie had spent her own formative years nearby, meeting friends in Lincoln Park—the same neighborhood where O’Malley would later take kung fu lessons and join lion dances, never realizing that, a century earlier, her great-grandmother had also walked those same streets.

Through Oakland Ilokana, O’Malley has created a real-time portal, allowing her to continually hear her lola’s voice. For her, the filmmaking process has been both a personal journey of healing and a gift to her family and community, preserving oral histories and emotional truths. This keen filmmaker’s engagement with her loved ones and community exemplifies intergenerational storytelling as a powerful tool for healing, identity, and social connection.

O’Malley on stage (Photo By Lisa Suguitan Melnick)

For those who may have missed the Oakland Asian Cultural Center screening event, Oakland Ilokana will be screened again on December 13, 2025 at the San Leandro Main Library.

“Oakland Ilokana” was produced in collaboration with Balay Kreative, the East Bay Foundation, and the City of San Leandro.

For more information about Elenita Makani O’Malley, visit: www.elenitamakani.com

Lisa Suguitan Melnick and Elenita Makani O’Malley (Photo by Alyssa Cortez)

Lisa Suguitan Melnick is a third generation Filipino-American of Ilokano and Cebuano roots. She is the author of #30 Collantes Street (Carayan Press, 2015). Her work is also published in Beyond Lumpia, Pansit, and Seven Manangs Wild,edited by Evangeline Buell et al (Eastwind wBooks, 2014) and The New Filipino Kitchen, edited by Jacqueline Chio-Lauri (Agate Surrey Press, 2018). She is at work on a new manuscript, Between the Lines.

More articles by Lisa Suguitan Melnick

No comments: