How Vietnam War Vets Wrestled with the Shadows of the Toxic Orange Mist

A U.S. helicopter spraying Agent Orange during the Vietnam War (Source: Wikipedia)

“Never again shall one generation of veterans abandon another.”

— Motto of Vietnam Veterans of America

Agent Orange: Origins and Deployment

The Vietnam War was not only waged with bombs and bullets, but also with chemicals and chromosomes. It was also a silent war waged against the land, people, and generations yet unborn. Among the many tools employed by the U.S. military to counter guerrilla insurgency, none left a legacy as insidious as Agent Orange, a dioxin-laced herbicide used to defoliate jungles, destroy crops, and deny the enemy concealment. The effort was codenamed Operation Ranch Hand, and it became the most aggressive and extensive chemical defoliation program in history.

The roots of Agent Orange trace back to British counterinsurgency operations during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960). There, British forces experimented with defoliants to destroy crops and jungle cover used by Communist insurgents. American military observers saw these efforts as a model for future warfare against guerrilla movements. When American involvement in Vietnam deepened, the U.S. sought ways to use technology to counteract the Viet Cong’s intimate knowledge of terrain and their ability to blend with the civilian population.

The ideological fervor of the Cold War made Vietnam a testing ground for both conventional and unconventional weapons. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy authorized the use of herbicides following lobbying from both South Vietnamese officials and Pentagon planners. Initially termed a "test program," it soon expanded. The chemical agents were sprayed not only over the Ho Chi Minh Trail and enemy-controlled jungle, but also over farmland and villages suspected of aiding the insurgency. These missions soon became routine. By 1962, Operation Ranch Hand had been formally launched under the 12th Air Commando Squadron of the U.S. Air Force.

Operation Ranch Hand (Source: U.S. Air force)

Composition and Deployment

Agent Orange derived its name from the orange stripe painted on its storage barrels. It was a 50:50 blend of two synthetic auxins, 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) and 2,4,5-T (2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid). The most lethal component, however, was not the herbicides themselves but a manufacturing byproduct—2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), one of the most toxic dioxins known. TCDD contamination was especially high due to the wartime demand that forced manufacturers to accelerate production without adequate safety measures.

From 1962 to 1971, nearly 19 million gallons of herbicides were sprayed over Vietnam. Agent Orange accounted for about 60 percent of this total. Spraying operations were done from C-123 aircraft, helicopters, boats, and by hand. The planes flew in formation, releasing clouds of chemicals over triple-canopy jungle, cropland, mangroves, and riverbanks. Entire provinces, particularly in the Central Highlands, Mekong Delta, and near the demilitarized zone (DMZ), were systematically defoliated.

Scientific Dissent and Public Awareness

Even before the escalation of herbicide use, scientists had warned of the potential dangers. Studies at Bionetics Research Laboratories and internal Defense Department memos highlighted birth defects in laboratory animals exposed to 2,4,5-T. Despite this, U.S. officials pressed ahead, prioritizing tactical gains over environmental or human health.

Dr. Matthew Meselson of Harvard University became one of the earliest and most vocal critics. In 1969, he publicly challenged the government's use of herbicides, calling it a violation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol. The same year, journalist Seymour Hersh published an exposé detailing the risks and long-term consequences of chemical defoliation in Vietnam. The story sparked national debate.

Veterans returning from Vietnam began reporting unusual symptoms—rashes, fatigue, headaches, and later, more ominous diagnoses like non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease. Initially dismissed as coincidental or psychosomatic, these cases formed the basis of later epidemiological studies. By 1970, opposition to Operation Ranch Hand had reached Congress. Hearings were held, but it was not until January 1971 that the Department of Defense officially suspended Agent Orange use.

Ecological Devastation

The impact on Vietnam’s environment was catastrophic. Once-vibrant forests were reduced to barren landscapes. Over 5 million acres of agricultural land and 500,000 acres of forest were affected. Mangrove swamps, critical to the ecosystem of southern Vietnam, were destroyed beyond recovery. Wildlife populations collapsed, and soil erosion intensified in once-stable jungle terrain.

Villagers whose livelihoods depended on fishing and rice cultivation found their fields poisoned and their water sources tainted. For many, illness became chronic. Reports of birth defects, miscarriages, and stillbirths in sprayed areas began to surface in the late 1970s and continued into the 21st century.

Vietnamese scientists, working with international NGOs and U.N. health agencies, later documented elevated dioxin levels in blood, breast milk, and soil samples in affected regions like Da Nang and Bien Hoa. Yet despite mounting evidence, the U.S. government long denied liability for civilian harm in Vietnam, claiming the sprays were directed solely at military targets.

Vegetation affected by Agent Orange (Source: ACES/Illinois)

Human Toll on U.S. Veterans

For American veterans, the toll was equally devastating. More than 2.8 million U.S. personnel served in Vietnam; it is estimated that between 2.1 and 4.8 million of them were exposed to Agent Orange. By the 1980s, class action lawsuits had been filed against chemical manufacturers including Dow, Monsanto, and 111 Diamond Shamrock. In 1984, the companies agreed to a $180 million settlement fund, but the agreement included no admission of guilt. Many veterans felt betrayed.

The Agent Orange Act of 1991 marked a turning point. It authorized the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to provide disability compensation for certain diseases presumed linked to Agent Orange exposure. The list of recognized conditions has since expanded to include over a dozen diseases, including chronic B-cell leukemia, Parkinson’s disease, and peripheral neuropathy. Yet, bureaucratic obstacles remained. Veterans bore the burden of proving their presence in sprayed areas, despite incomplete or inaccurate military records.

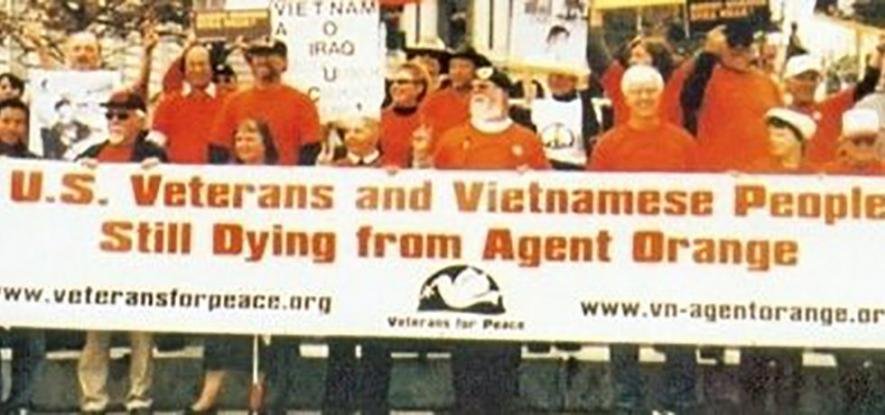

The legacy of Agent Orange continued to draw condemnation. The Vietnamese Red Cross estimates that over 3 million Vietnamese people have been affected by dioxin, including more than 150,000 children born with severe birth defects. Efforts by Vietnam Veterans of America and other advocacy organizations have brought attention to the transgenerational effects of exposure.

A deformed Vietnamese man who was in his mother’s womb when she was exposed to Agent Orange (Source: Wikipedia)

Cleanup efforts began in earnest only in the 21st century. With funding from USAID and assistance from the Ford Foundation, remediation projects were launched in heavily contaminated "hot spots" such as Da Nang and Bien Hoa. Technologies like thermal desorption and bioremediation have shown promise, but progress is slow and expensive.

Personal Encounters and Medical Aftermath

For U.S. Marines and soldiers on the ground, the orange mist was often invisible, its impact unnoticed until years, sometimes decades, later. I was a Staff Sergeant, a Marine non-commissioned officer who served as part of a Combined Action Program (CAP) unit. My exposure to Agent Orange was not a matter of “if,” but “how much.”

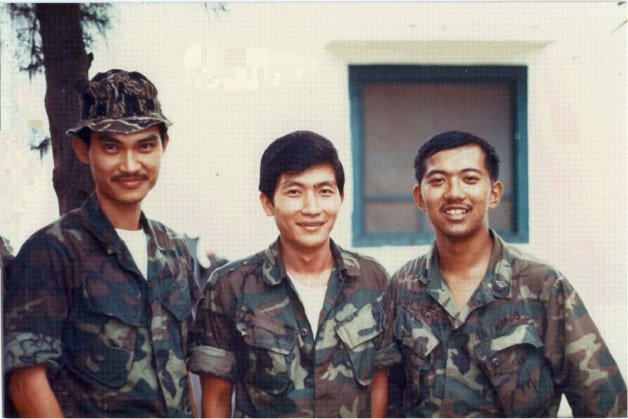

Staff Sgt. Alex Fabros, Jr. during his time in Vietnam (Photo courtesy of Alex Fabros Jr.)

I arrived in Vietnam in 1969 and was assigned to a CAP unit in I Corps, near Da Nang, an area later identified as one of the most heavily sprayed regions during the war. CAP Marines lived, patrolled, and fought alongside South Vietnamese Popular Forces in rural hamlets, frequently in areas subjected to chemical defoliation under Operation Ranch Hand. Though Agent Orange missions targeted jungles and suspected Viet Cong (VC) strongholds, nearby villages and farmlands were often collateral damage.

Fabros with fellow soldiers in vietnam (Photo courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr.)

As a Chinese Mandarin- and Vietnamese-speaking Marine trained in combat interrogation at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, I frequently accompanied patrols and supported civil-military operations. I also assisted with Medical Civil Action Programs (MEDCAPs), bringing basic healthcare to remote villages. These efforts, part of a broader civic action initiative, were designed to win “hearts and minds” of the rural Vietnamese population, while simultaneously denying the VC their base of support.

Defense Language Institute

One such MEDCAP mission took me to a village at the foot of the Ba Na Hills—a quiet, isolated hamlet nestled among bamboo groves and rice paddies. The villagers had never encountered Americans before. To ease the tension, I used brightly colored band-aids to treat minor wounds. A young girl and her brother approached me cautiously. I gently applied yellow bandages to their arms. A few days later, after a Viet Cong raid, I returned to find those same children dead, marked by the yellow bandages I had placed. I never forgot the children’s faces. For me, those yellow bandages became a symbol of the war’s bitter paradox—how mercy could become a death sentence.

The Air They Breathed, the Water They Drank

Marines were told the herbicides were harmless to humans. Later scientific surveys revealed that areas around Da Nang Airbase, where I frequently operated, were among the most heavily contaminated in Vietnam. We didn’t know what we were walking through, I later recalled. Everything looked dead. But we thought that was the point.

In 1970, I collapsed during a patrol and was Medevacked to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Yokosuka, Japan, where I was treated for inflamed skin lesions with high-dose corticosteroids. While recovering, I enrolled at the International Christian University in Tokyo to study Japanese. This academic detour marked the beginning of a lifelong commitment to Asian and Pacific studies.

I returned to the U.S. and was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps at Treasure Island on 27 May 1971. For the next nine months, I sailed solo across the Pacific on my 30-foot Coronado sailboat, reflecting on the war and my future.

In February 1972, I enlisted in the U.S. Army, graduated from OCS in November, and completed the Armor Officer Basic Course in 1973. I was then assigned to duty along the Korean DMZ, another zone affected by defoliant spraying. I returned to Korea in 1980–81, serving again near the Chorwon Valley, an area long suspected of post-war chemical contamination.

The long reach of Agent Orange did not stop with me. Both my son and daughter were born with minor birth defects, one neurological, the other connective tissue-related. Doctors, noting similarities in other children of Vietnam veterans, believed the anomalies stemmed from dioxin-linked epigenetic inheritance.

Soldiers check for unexploded mines and agent Orange in Da Nang City (Source: VOA)

Chronic Illness, Bureaucratic Resistance

Following my military retirement in June 1992, I became affiliated with the San Francisco State University and was accepted into the UC Ph.D. program in history, bypassing formal degree requirements. My life experiences, language fluency, and archival skills earned me the UC President’s Five-Year Fellowship in the Humanities.

I had been diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in 1974, a condition that returned in 1991 and remained active until remission in 2003. I suffered my first heart attack in 1990, and since retirement have endured 14 major heart attacks, requiring open-heart surgeries in 2006 and 2022.

I filed for VA disability compensation, seeking recognition that my Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and heart disease were service-connected. At that point, my NHL, already diagnosed in 1974 and again in 1991, had taken a serious toll. I was undergoing chemotherapy while teaching and conducting graduate research. Both claims were denied.

Despite a clear service history in I Corps–one of the most heavily sprayed areas in Vietnam–and mounting scientific evidence linking dioxin exposure to cancers and cardiac issues, the VA denied my claims. They cited a lack of “sufficient evidence” to prove that my illnesses were “service-connected.”

I was told to provide unit records, herbicide exposure documentation, and proof that I had been in specific sprayed zones at specific times—requirements that were both logistically and scientifically unreasonable for veterans of the Combined Action Program, who had no control over defoliation schedules or aerial spraying patterns. They were asking me to prove where a cloud had drifted 30 years ago.

However, the VA rated my Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) at 100 percent, acknowledging the psychological toll.

The distinction mattered deeply. Conditions not deemed service-connected provide no survivor benefits, including Dependency and Indemnity Compensation (DIC). It’s hard to die from PTSD—but Agent Orange will kill you. For me, service connection meant more than compensation, it was about justice and my family’s future.

Fight for Recognition

(Source: Global Ecology Project)

The fight for recognition–one waged not in jungles or on ridgelines, but in administrative offices and examination rooms–for validation that my illnesses were a direct consequence of my service in Vietnam–would last for decades and expose the deep flaws in the way the United States government responded to the long-term consequences of Agent Orange.

I was not alone. Across the country, Vietnam veterans encountered a culture of skepticism and institutional inertia within the VA. Thousands had similar stories: denied claims, years-long appeals, and shifting eligibility standards. For CAP Marines and Army advisors who had operated in rural areas outside of major bases, exposure was obvious, but paper trails were often non-existent.

Even though Congress had passed the Agent Orange Act of 1991, establishing a list of presumptive diseases tied to herbicide exposure, implementation was slow, and new conditions were only added after intense lobbying, lawsuits, and years of medical review. My own conditions, Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and ischemic heart disease, were only added to the presumptive list after I had already lived with both for decades.

In the interim, I paid out of pocket for care, relied on university health services when teaching, and navigated a fragmented system that often failed to see the whole of my medical and military life.

Recognition, at Last

Despite the rejections, I continued to document my medical history, gather medical records, and connect with other veterans affected by Agent Orange. I became deeply involved with Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), an organization that led the charge to expand the list of presumptive conditions and reform the claims process.

In 2022, the PACT Act (Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics) was passed by Congress, further expanding VA health care and benefits for veterans exposed to toxic substances, including Agent Orange. It marked one of the most significant legislative victories for veteran advocacy in decades, reflecting a growing national awareness of the hidden costs of war.

“The long reach of Agent Orange did not stop with me. Both my son and daughter were born with minor birth defects, one neurological, the other connective tissue-related.”

The passage marked a turning point. It finally designated Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and ischemic heart disease as presumptive service-connected illnesses linked to Agent Orange. My illnesses, once denied, were now presumptively recognized as service-connected, restoring dignity and securing future protections for my survivors. This legislative victory was not just a policy shift; it was a moral affirmation of the lived reality of thousands of veterans.

Today, I serve as President of the VVA chapter covering California’s Central Valley and as a Director of the California State Council of the VVA. Through these leadership roles, I have helped countless fellow veterans navigate the complex bureaucracy of VA healthcare and disability claims.

As I said at a VVA conference, it's not just about me. It's about those who died waiting. It's about the families who were told it wasn’t real. It’s about finally being heard. My case, like so many others, exemplified the intersection of silence, sacrifice, and systemic neglect that defined the postwar experience of Agent Orange exposure.

Legacy and Lessons

Today, I continue to speak publicly about the long-term effects of chemical warfare and veterans’ rights. I returned to Vietnam in 2018, where I witnessed children still suffering from Agent Orange–related deformities. The visit reinforced my conviction that the fight must continue not just for veterans, but also for the Vietnamese victims and future generations.

My fellow veterans and I now support a children’s hospital near Da Nang, fund scholarships for dioxin-affected youth, and serve as witnesses to history. The war may have ended in 1975, but the consequences of Agent Orange span generations.

I remain adamant: We were poisoned in silence. Our healing must be heard out loud.

SIDEBAR

Approximately 2.7 million Americans served in Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

Here are more detailed figures:

-

Total U.S. military personnel who served in Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and adjacent waters) during the Vietnam War (1964–1975): roughly 8.7 million

-

Number who actually served in the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam):

About 2,709,918 men and women in uniform

(This figure includes those who served at least one duty tour in Vietnam.)

Additional Breakdown:

-

Peak troop strength in Vietnam:

543,482 in April 1969 -

Total U.S. military deaths in Vietnam:

58,220 -

Total U.S. military wounded in action:

304,000+ -

Percentage of U.S. military who served in Vietnam:

About 10% of the 27 million Americans who served in the U.S. armed forces during the Vietnam era (1964–1975).

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.

No comments: