New Cardinal Pablo Virgilio David: Just call him Apung Ambo

Cardinal Pablo Virgilio David (Source: UCANews)

Popularly known as Bishop Ambo, the populist priest mulled his recent promotion in a Facebook entry, “Of titles and designations.” The eminently educated and qualified cardinal wrote that he would rather not be called “Your eminence,” as princes of the church are usually addressed.

“If you want me to frown at you, call me ‘Eminence.’ If you want me to smile at you, just call me ‘Apung Ambo.’”

Apung is a Capampangan word of respect, an honorific used in addressing an elder or a superior.

It is very much like Bishop Ambo, a towering, authoritative but gentle and humble presence in the church, to understate the title of the high office that has been bestowed on only ten Filipino bishops.

Cardinal David with Pope Francis (Source: Inquirer.net)

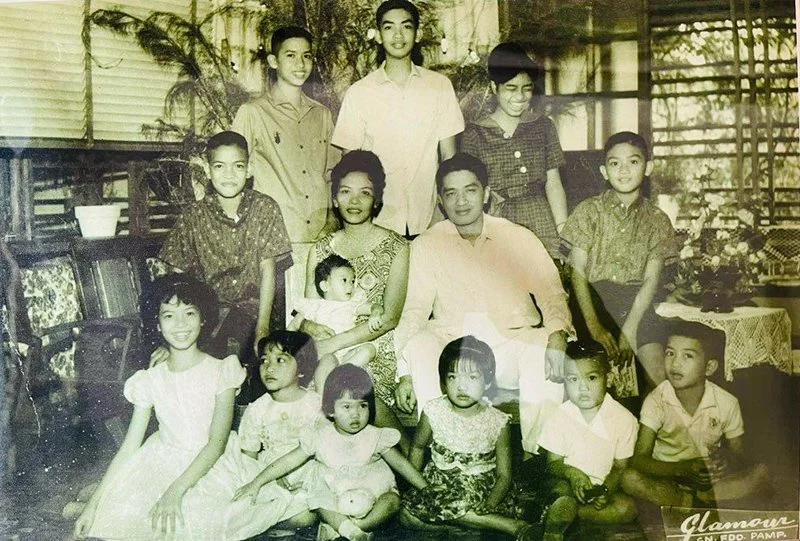

A native of Pampanga, Pablo Virgilio David was born in Betis, Guagua on March 2, 1959, the 10th of 13 children of Pedro David, a lawyer, of Betis, and Bienvenida Siongco David of Macabebe. Betis, like Lubao, was once a royal encomienda and was under the direct supervision of Governor General who ruled in the name of the king. It is where the Augustinian priests built the first churches in the Philippines and the two towns became strongholds of Catholicism in the Philippines.

As such, the tradition was that every family was expected to contribute one of its children to the priesthood or the nunnery. UP Sociology professor Randy David, the eldest of the David siblings, recalls that growing up in Betis, every other family in the town had a priest or a nun.

In the David family of seven boys and six girls, the four oldest sons felt the pressure of being groomed for the priesthood. The practice was to invite the boys from the village to spend a week or two at the Mother of Good Counsel Seminary in San Fernando to see if the priesthood interested them. The older boys went, but no one was interested. And none of the girls showed an inclination towards convent life either. “And so we were relieved of the pressure,” says Randy.

Then Ambo came with a vocation so natural and spontaneous, ensuring the family’s contribution to the tradition in their town.

Their parents were religious. Bienvenida was a member of the Catholic Women’s League. But they were liberal, and the children were brought up in a secular manner. What the children learned early on was the importance of family and the need to take care of one another.

When Randy left home to study in UP for college, Ambo was just two years old. But since Ambo entered the priesthood and rose in the ranks, they have gradually become peers. Says Randy, a noted sociologist, their disciplines are closely related, he being the “secular half” to Ambo’s theological, spiritual, and philosophical side.

Like his elders, Ambo started first grade at four years old. Randy explains that in Betis, the public school near their home was like a day care where the children were sent at an early age to relieve their mother of having to care for so many of them at home.

Early Vocation

Ambo’s vocation manifested early in childhood. From his catechism class, he learned that Jesus was present in the Holy Eucharist in the tabernacle, and the burning vigil lamp in the church indicated His presence. When the lamp was not burning, he was told, it meant that Jesus was not there.

When Ambo walked to school, he would stop by the church to see if the vigil lamp was burning and say hello to Jesus. And he would do the same on his way home. One day, he panicked when he saw that the tabernacle was open, and the vigil lamp was not lit. Running home, he told his mother that Jesus was gone. She explained that the parish priest had been taken ill and there was no priest to say mass, and when there was no mass, there was no Eucharist.

That was when he told his mother that he wanted to be a priest. She approved but he had to finish the elementary grades first. He was ten-years-old when he finished Grade 6 and entered the Mother of Good Counsel Minor Seminary in San Fernando for high school, where he graduated as valedictorian after four years. At age 14, he was accepted at the San Jose Seminary in the Ateneo de Manila.

Quest for Relevance

Thus Ambo’s journey for relevance began. It was 1973, the nation was under martial law. According to Randy, the Ateneo radicalized the young Ambo. The campus was in ferment. He joined nationalist groups, learning about social inequality, the rot in the political system. On the year before his ordination, Ambo was sent back to his diocese to determine with finality if he really had the vocation for the priesthood.

In San Fernando, Ambo was assigned to assist parish priests in peasant communities in far-flung areas in Pampanga where he got even more radicalized.

Ten years later, on March 12, 1983, after completing his studies at the seminary and having gone through Theology at the Loyola School of Theology, Ambo was ordained at the San Jose Seminary, at the age of 24.

After ordination, Ambo was sent back to Pampanga, to serve in a middle-class parish, for obvious reasons. He was also assigned as Academic Director of his old school, the Mother of Good Counsel Seminary.

But the young radical priest’s quest for relevance continued. He felt that he belonged not inside the church, but outside, with the faithful. He wore his hair long and got deeper into activism. Worried that her son might get into trouble with the military, his mother asked Randy, who was a professor at the UP, to talk to Ambo.

Randy put things in perspective by giving him the lay of the land: the different ideological groups operating against martial law, their belief systems, their political aims. His advice to the young Ambo: Do not make the mistake of going underground.

Advanced Studies in Louvain

The “problem” of Ambo’s embrace of activism was resolved when Archbishop Oscar Cruz, who was then archbishop of Pampanga, found a scholarship for him to go abroad for further studies. Ambo didn’t want to leave but he had no choice. \ He chose to go to the progressive Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium.

Ambo was away until 1991, pursuing his Licentiate and later a Doctorate in Sacred Theology at Louvain. His studies brought him to Jerusalem and Jordan where he learned Aramaic for his dissertation on the Book of Daniel.

Upon his return to the Philippines, he was appointed parish priest of San Fernando and taught in his old seminary where he encouraged his colleagues to pursue further studies in Louvain. In 2002, he was named director of the Department of Theology at the seminary, teaching Sacred Scripture for 17 years. He also taught at the Loyola School of Theology on his specialty, the Old Testament.

Apung Mamakalulu

On May 27, 2006 he was appointed Titular Bishop of Guardialfiera, a small, picturesque town outside Rome, and Auxiliary Bishop of San Fernando, by Pope Benedict XVI.

In San Fernando, he did whatever was assigned to him by the archbishop. Wherever he went, Bishop Ambo took care first of infrastructure. Says Randy, “Ambo is an artist who excelled at redesigning homes, refurbishing and repurposing old structures where he was assigned, except in Kalookan where he was too busy defending his parishioners from the oppression of the drug war.”

His next assignment was the city of Angeles where he noticed that the marginalized communities, those who lived in the periphery, did not join the well-heeled at mass in the cathedral. They went instead to a nearby shrine, the Apung Mamakalulu or Merciful Lord, built by a local family that housed an image of the Santo Entierro (The Dead Christ), the exact copy of the image that was in the cathedral, that the people believed to be miraculous.

The shrine was privately owned by a local family who collected rent from the market vendors and stall owners that had sprouted in the area. Beside it was a mansion that had gone to seed. People lined up to give money and put letters in a hole at the foot of the glass-encased statue and then whispered their prayers, verbalizing their grief, at the ear of the Santo Entierro.

Ambo was determined to integrate this community and its folk religion into the flock.

He offered to buy the property. When he found out that the property had been pawned to a bank and could no longer be redeemed, and the bank had plans to sell it to a mall developer, he argued that Apung Mamakalulu was a holy site, and converting it into a giant mall would violate the people’s beliefs. He asked the bank to sell it to the church instead at its original prize with the interests waived.

He raised the money, starting with his 12 siblings whom he asked for donations equivalent to the cost of one square meter each. He also organized the Singing Priests, a group of clergymen who sang, that held concerts all over the country to raise funds.

Ambo raised more than enough to pay for the real estate and the mansion next door. He mobilized his brother Nestor, an architect, to redesign the area and the shrine. The mansion was refurbished to become the house of the parish priest.

Going to the Periphery

On September 14, 2015, he was appointed by Pope Francis as the Bishop of the Diocese of Kalookan. Vacant since 2013 when the Bishop resigned due to poor health, the diocese encompasses the cities of Malabon, Navotas, and Kalookan where over a million Catholics reside. It has been the most challenging assignment for Bishop Ambo. It is also where he found his true calling.

There he found relevance in what Pope Francis has been saying to priests, to go to the peripheries. In Kalookan, where the cathedral is surrounded by slums filled with internal migrants, the so-called laylayan, the last, the least, and the lost of the metropolis, he realized that the poor had little sense of community and felt ignored and forgotten by the church.

Former President Rodrigo Duterte’s infamous “war on drugs” was at its height, which led to the extrajudicial killing (EJK) of over 12,000 (some say as many as 30,000) Filipinos, mostly from the urban poor. He had to find a way to bring the Church closer to the poor, uplift the spirits of the EJK families, and empower the poor communities against injustices and social issues. Bishop Ambo transformed his diocese from a “maintenance” church doing business as usual to a missionary church – an active response to Pope Francis’ call to “go to the periphery.”

In 2017, to further bring the church to the poor, he invited religious, diocesan priests, and lay communities to establish urban mission stations in poor communities in Caloocan, Navotas, and Malabon to accompany, protect, and empower them from the rampant extrajudicial killings. At present, there are 21 mission stations in the Diocese of Kalookan, including those established by volunteers from Latin America, South Korea, and India who, inspired by Bishop Ambo’s innovation, have established their own mission stations in the area.

Kalookan was Ground Zero for extrajudicial killings of alleged drug users and dealers by police and vigilantes, and Bishop Ambo, himself a vocal critic of the drug war, was publicly singled out by Duterte for censure and was in the vigilantes’ crosshairs.

His sisters begged him to be careful, to stop his predictable activities where he could be harmed, such as praying the rosary in the evening while walking around the church compound accompanied only by his pet dog. “God will protect me,” he assured his siblings.

They trembled at headlines from the Palace that threatened his life. “Wag ka na kasing magsalita,” they said. “Isang bala ka lang (Don’t speak out. You’re just a bullet’s worth).” His response, “Kung hindi ako magsalita, sino ang magsasalita (If I don’t speak out, who will)?”

One of the Girls

If Bishop Ambo has underplayed his title from Eminence to the more familiar Apung, among the younger half of his family, the four sisters whom he grew up closely with, he is just “one of us girls.”

Says his youngest sister, Marivic, a dentist, “He left the family early, but prior to that, we were playmates. We all had our household chores like sweeping the floor and gardening.” So up to now they have the same passion for gardening that they do a lot of together when she visits him at the Bishop’s Bahay Pari in Bataan. “And when I leave, he fills my car with plants.”

Marivic recalls how Ambo was the only one of her brothers who could be counted on to do his share in caring for their mother when she was ill, doing hospital duty, like the girls. “We could tell him what he needed to do to take care of our mother, including cleaning her and changing her clothes and he would do it.”

It is very much like Bishop Ambo, a towering, authoritative but gentle and humble presence in the church, to understate the title of the high office that has been bestowed on only ten Filipino bishops.

“Humble and selfless and very sweet,” Ambo always brings something for his siblings when they meet, like Itlog na maalat (salted eggs), hopia (mung bean cakes), mangoes.

The David siblings are closely knit. Marivic says, “We protect each other. We take care of each other. Our parents never told us to, but we were brought up that way.” It is also quite hierarchical. So, while Ambo is a bishop and soon to be a cardinal, he is just one member of the big and diverse clan. On family matters, the eldest, Randy, remains the top authority.

However, everyone accedes that Ambo has a special place among the siblings. The spiritual center of the family, he is the mediator, gentle and easy to approach, when conflicts arise.

While his siblings say their parents played no favorites; they were busy enough raising 13 children, Marivic recalls: “Our mother used to say of Ambo with pride, ‘Itong anak ko ay pari (My son is a priest)’ We didn’t see her doing that for any of her other children.” She also hoped that one day, her son would become a cardinal.

Now, her tenth child, Pablo Virgilio, is a cardinal, a prince of the Church. But special as he is, in the family, he remains just one of her 13 children. And please don’t call him “Your Eminence.” Apung Ambo will suffice.

For more on Bishop Ambo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFGGtJyPrtA

Paulynn Sicam is a retired journalist, sometime columnist (for the Philippine Star), and freelance book editor in Manila.

More articles from Paulynn Paredes Sicam

No comments: